All Rights are Reserved to the author of this contribution.

The weird + eerie:

an interview with Lawrence Lek on crossing the line + exposing the deeply embedded through VR

Lawrence Lek, interviewed by Henry Broome for AQNB, 13 June 2017

“For me, the simplest utopian experience is your point of view,” says Lawrence Lek, looking across at London’s Olympic Park from the window of his studio. “Whether from the Eiffel Tower or the Orbit, it’s a privilege to be a certain place and look somewhere.” Access to the stadiums is highly restricted, there’s a charge to summit Anish Kapoor’s tower, and the parkland around is monitored by guards and CCTV.

In our interview Lek recalls his studies in architecture in the British capital, as well as his interest in the social implications of space and its utopian potential, “but after a while of working in architecture firms you realise that’s not really on anyone’s agenda.” As an artist, he uses gaming software to build immersive virtual worlds, employing the tools of architecture without using real world “territorialisation.” In ‘Delirious New Wick’ (2014) – part of the virtual reality (VR) gaming series called ‘Bonus Levels (2013 – present)‘ – the player can roam the Olympic complex without restriction. “Access is a political act and it can be a transgressive act as well,” he says about VR and its potential, “with the idea of private property, the number one thing is ‘do not cross this line’; so in my work I’m super interested in crossing that line.”

Lek was born to Malaysian-Chinese parents in Frankfurt but spent his formative years in Asia. Growing up in pre-handover Hong Kong and Singapore (which celebrated its independence in 1965), he developed a hypersensitive awareness of how neoliberalism and nationhood shape geopolitical interactions between the East and West. ‘Sinofuturism’ (1839 – 2046 AD)’ (2016) interrogates how Western media, the BBC and Infowars particularly, schematise Chinese society. The video essay identifies seven stereotypes of China: Computing, Copying, Gaming, Studying, Addiction, Labour and Gambling. Similar to Afrofuturism or Gulf Futurism, Sinofuturism adopts and subverts these cultural clichés, analogising these preconceptions as forms of machine learning and technological development.

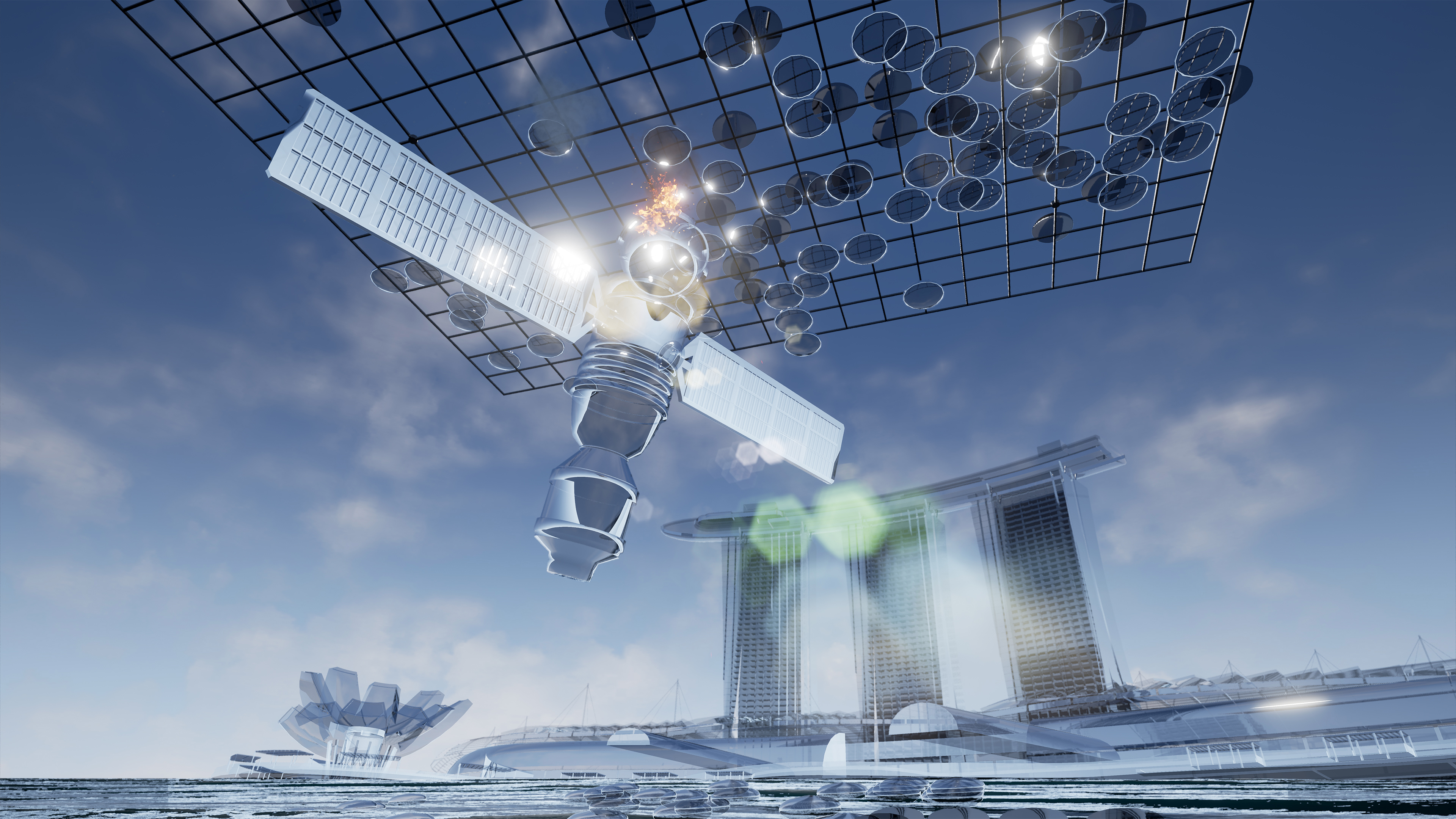

As winner of the 2017 Jerwood/FVU Award, Lek was commissioned to produce ‘Geomancer’ (2017). Whereas ‘Sinofuturism’ gave humans robot properties, ‘Geomancer’ anthropomorphised artificial intelligence (AI). The 48-minute “mini-opus” follows a weather satellite of the same name who possesses human self-awareness and emotion, and can even dream. Lek says the premise is strongly related to Zhuangzi’s tale of The Butterfly Dream, where a man wakes from dreaming he was a butterfly not knowing whether he is a man or a butterfly, dreaming he is man.

In Lek’s work, not only is it ambiguous what’s AI or human but also what is real or virtual. In Unreal Estate (The Royal Academy is Yours) (2015), produced for the 2015 Dazed Emerging Artist Award, he positions the viewer as the new owner of London’s Royal Academy of Arts – a fantastical proposition, but one that appeals to our deepest desires ‘to live in a palace.’ Lek relates the situation to The Weird and the Eerie (2016), a book by the late theorist Mark Fisher, telling me, “I try to construct scenarios where there is enough weird and eerie stuff so that people that come across my work really feel like this world is made for them. That’s why I’m doing what I’m doing.”

HB: Most of your work can be accessed online, via Vimeo, free of charge. You also satirise the notion of cultural ownership in ‘Unreal Estate.’ Do you advocate a system of art that abandons ownership?

LL: I don’t have this overarching ambition to eradicate some kind of evil hierarchy of art ownership. It just doesn’t cross my mind. For me, I’ve been lucky enough to be paid to produce this weird eerie stuff. I would like people to see it if it’s interesting to them.

HB: Do the people that commission your work have a problem with you uploading it online?

LL: I’ve never had any issues, but maybe that’s because of the specific means of production in the visual culture industry. As an emerging artist, there’s no intrinsic value to the digital media I have produced because most of these works are site-specific, in the sense that they are produced for Glasgow International or the Dazed show. Outside of that time frame, the institutions don’t really care. In the most unromantic sense, what if I’m just a content producer for the cultural industries? Without romanticising the life of an artist, that’s what I am, right? That’s the unwritten contract. I’m passionate about not being naïve about these processes, but accepting it because it lets me produce what I hope is good art. Good art might be partly about institutional critique, but more importantly it’s about owning the world that your work exists within. But past a certain point we are all dependent on both non-profit goodwill and for-profit enterprise. So I’m very interested in examining our love-hate relationship with the institutions that both propel and chain us to the search for a better life.

HB: Tell me how the idea behind ‘Sinofuturism (1839-2046)’ (2015) came about.

LL: It was while I was doing a residency at Wysing Art Centre – doing research – that I realised everything I was doing with AI and geopolitics, China and technology, was really a mirror image of each other. Sinofuturism is a diffuse kind of movement. As I say at the beginning [of the video essay], “it’s an invisible movement,” because it’s something that’s everywhere but never explicitly identified. ‘Stereotype’ is a really charged term. I use stereotypes to look at deeply ingrained cultural patterns, so deeply embedded that they are otherwise unidentified.

HB: Do you think by adopting replication as a Chinese characteristic, among other stereotypes, that the notion of Sinofuturism creates even greater polarity between East and West?

LL: ‘Polarisation’ isn’t the way I see the world. I see different worlds nesting within one another. At the end of Sinofuturism, I say, “in the West the East is the Other; in the East the West is the Other.” It is a relativistic mode of thinking, as opposed to an oppositional one. I just say this from my position from having both these cultures embedded in my mindset. As a third generation overseas Malaysian-Chinese, I at least have the privilege of being self-aware about these things.

HB: In ‘Geomancer,’ the viewer follows a weather satellite called Geomancer around Singapore. In one exchange between Geomancer and another AI, it’s asked “Can you smell the jasmine in springtime” – a question that curator AI can’t answer. It’s reminiscent of the opening scene in Blade Runner (1982) where a replicant robot is unable to answer abstract questions about human sense and emotion, one in particular about its mother. How have sci-fi movies, and perhaps that scene from Blade Runner, informed how your work approaches debates of AI sentience?

LL: I’m glad you picked up on that one. ‘Can you smell the jasmine in springtime’ is just the most hyper-poetic question you could ask, somehow. Obviously, this satellite AI hasn’t smelt the jasmine in springtime because it’s been on earth for about 40 minutes but it’s also just about the limits of sensorium of any thing, any conscious entity.

In terms of influence of other science fiction films, or films in general, one of my favourites is The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser by Werner Herzog. Hauser was a real young man who, up until he was found at 18 or so, had never had any human contact. He was totally wild. Kaspar Hauser just turns up one day in the middle of this German village and he is confronted with human society and being put on show, like this freak for people to see as he learns to talk, to write and play the piano. It’s really a portrait of someone who goes through this accelerated adolescence. In a way though, I wasn’t thinking about it so explicitly in Geomancer, that’s the closest thing I had to a model for how this super intelligent AI would fare if they came down to earth and were confronted with something completely unfamiliar.

HB: Are you a technological optimist? I think it’s possible to be both worried and hopeful about the future of technology.

LL: It’s definitely both of those things. The problem is there will always be an economic incentive to automation because it’s cheaper and works 24-7. In my practice, I try to think about the implications of technology as objectively as possible. People are invested in it, so we’ll have more of it. What I’m interested in my artwork is the unknown forms of beauty and pleasure that technology is going to create. With Geomancer, for example, can you imagine, can you conceive what it’s like if you saw, perceived, recorded every wave on the ocean and remembered it forever? Even just thinking about that, it’s unfathomable to us.

HB: There is a lack of human presence in your work. Is this a rendition of the Singularity – a theoretical future where humans have been replaced by AIs?

LL: It’s not an illogical conclusion but if you walked through a London street at four in the morning and there’s no one around, you wouldn’t think ‘everyone’s died and been replaced by robots!’

HB: Of course!

LL: I guess there are two sides to this; one, is the idea of simulation and the other, what Mark Fisher called the difference between the weird and the eerie. Firstly, I’m drawn to the first person perspective, the flâneur, and its atmosphere and sensibility. I find when confronted with an empty city or a ruin, or a sublime landscape, we see ourselves quite clearly – that poetic idea of personification in a landscape. Letting the internal monologue run wild is really generative for me as an artist. With Unreal Estate, if you were to look at it as an institutional critique, which is the surface level, you’d think ‘the artist does not think this great institution should be for sale.’ A deeper level – a deep desire that we all share – would be to live in a luxurious surrounding. That is the unspoken desire for revolution. We want everyone to prosper. I want to prosper. I want my family to prosper. Thinking honestly, of course, it would be ridiculous to own a Jeff Koons bunny but I would also love to be in a situation where I could afford one, you know, just snap my fingers, and get a couple of Ferraris. […] It’s linked to the utopian idea of access.

In the middle of Geomancer, the AI asks “Do I really belong here?” This idea of alienation is really important for me, and it’s related to Mark Fisher’s idea of ‘the weird’ versus ‘the eerie’. ‘The weird’ is something that is present but seems strange because it appears out of place, like an alien spaceship on earth. ‘The eerie’ is more to do with a sense of strangeness because something is absent. London totally evacuated, that’s eerie. It’s a helpful binary opposition in my own work. Let’s say I have a virtual world, you start with nothing, and so everything you put in has a strange presence. I try to construct scenarios where there is enough weird and eerie stuff so that people that come across my work really feel like this world is made for them. That’s why I’m doing what I’m doing.