All rights reserved to the author of this contribution.

The Life and Death of Anatomy

Nina Sellars

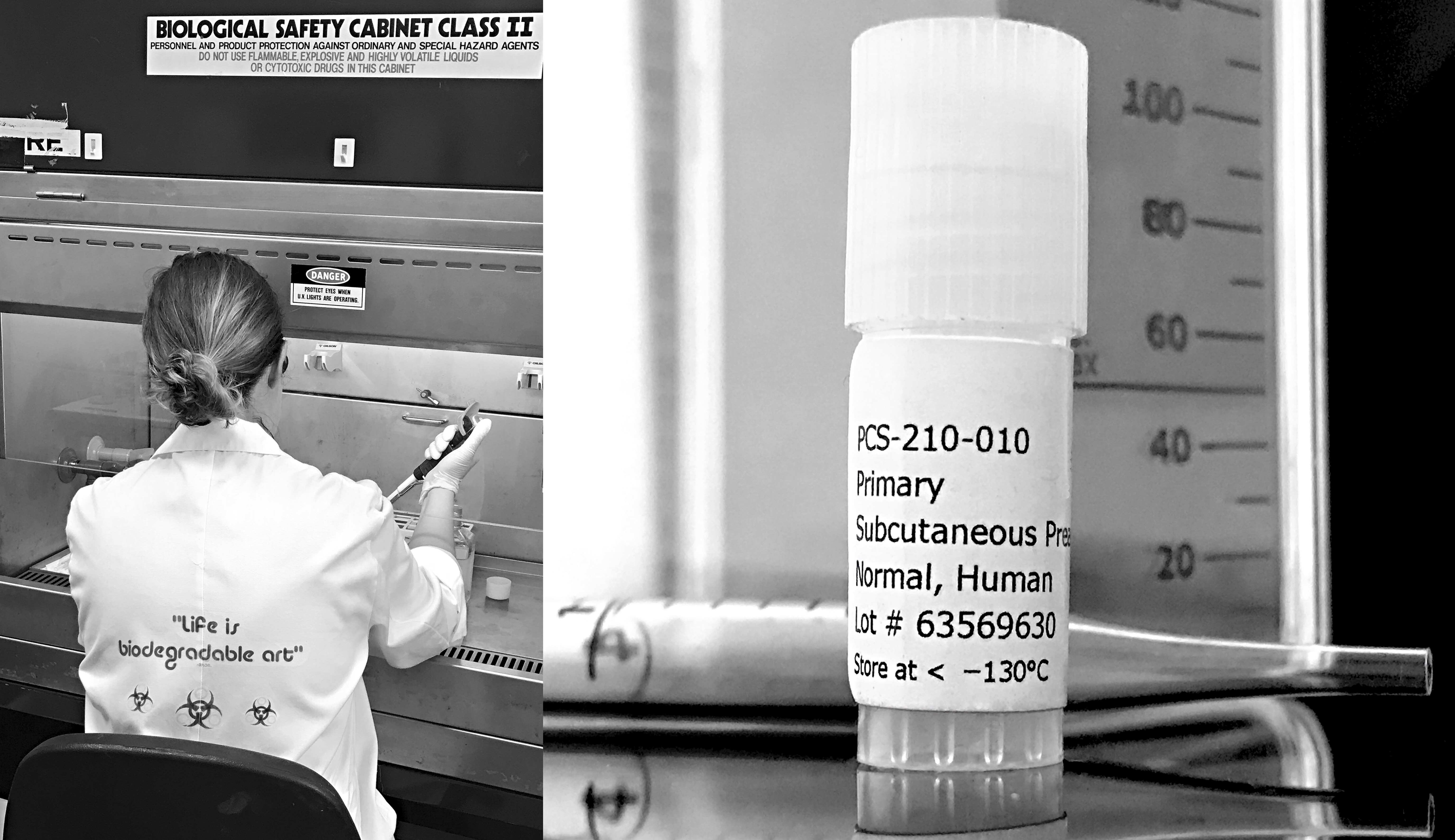

Nina Sellars working on adipose tissue culture for her project, ‘Fat Culture’, while artist in residence at SymbioticA, UWA, 2017. Photographers: Nina Sellars & Ionat Zurr. This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Life

In an era when virtual anatomies circulate on the internet and bioengineered human organs are being printed from volumetric images, it can appear that the various new modes in which we engage with anatomical images of the body are effectively redefining what it means to be human. A way of seeing becomes a way of being, whereby images no longer depict reality but can be thought of as actively determining the flesh of our reality. The images also seem to reveal a desire to design the human anew.

Yet, irrespective of the technological sophistication experienced in our engagement with contemporary anatomical images, there appears to be a certain recycling of what is essentially a 16th-century vision. Indeed, the fundamental propositions of Humanism that serve as the foundation of anatomy have remained relatively intact since the Renaissance. For example, evidenced in the visualisations of anatomy, which describe composite bodies of hylomorphic bounded volumes, ordered in Cartesian space. In other words, the body imagined as a machine-like assemblage of organ-ised parts. Arguably, life in the 21st century calls for a far more complex understanding of the human body, to bring into question the certainty of its boundaries and its movements in and with the world more generally.

If we want to take the idea of redesigning the human seriously, do we need to call for the death of anatomy as our normative frame of reference? And, if so, what approach would we need to take to engage in such a project, and what would these new humans look like? Could we even begin to imagine ourselves otherwise? Every breach of a perceived classification requires a renegotiation of relationships and understandings, which takes time, care and consideration, regardless of whether this act occurs at the level of the microscopic or at the level of social concerns. Indeed, it appears easier for us to imagine the disintegration of an individual (anatomical) body through death than to imagine the end of anatomy as the definitive framework of our being.

Death

Life moves through us and, at some point, lets us go. Matter scatters. The loosely bounded identity of the individuated human departs in a process of becoming-absence, and of becoming-other. Life flows on, taking with it the prior assemblage of matter that we and our loved ones had grown fond of, the ‘us’ of our particular being. Now, as before, and into the future, new alliances of matter are to be forged through happenstance in the life-death continuum. In this way, life consists of mattering and scattering, loss and continuance, seen not as isolated occurrences but as ‘waves of becoming’1.

If we view this realisation as an affirmative statement, and as a way of providing us with an opening onto what is possible, we can begin to question the boundaries of Humanist anatomy and go beyond – to explore notions of the posthuman. Though it should be noted, the volition and agency being expressed in our desire to redesign the human seemingly announces we are once again embarking on a Humanist project. But for now, holding onto the idea of us existing as incidental matter helps to release us from the certainty of anatomy’s bounded forms; it also presents the body as evolving with the world, i.e. all other matter, in each and every moment.

Anatomy

Do we need to overturn the project of Humanism to rethink anatomy? Ultimately, Humanism does have its charms. Here, I have to admit I have been somewhat invested in the project of anatomy and its Humanist conventions, in my previous employment as a body dissector and anatomical illustrator in a university medical school. Indeed, my aim is not to abandon Humanism, but rather to challenge it from within. In doing so, I adopt a critical posthumanist stance toward the science of anatomy, not only as a way to de-naturalise the Humanist framework of anatomy, through which we humans see and understand ourselves, but also to seek out the omissions and assumptions that occur in the enactment of anatomical knowledge. Here, I want to put forward adipose tissue (aka fat) as a matter of interest, and as a way of thinking of anatomy, differently. Indeed, I consider fat as a critical organ of posthumanism.

In the contemporary study of anatomy, fat is being reclassified as a complex distributed organ of the endocrine system, yet historically fat in anatomical imaging has been subject to systematic erasure. There are no chapters dedicated to fat in any standard text of anatomy. Even illustrations in classical anatomy atlases, for instance in Gray’s Anatomy, which is currently in its 41st edition, are characterised by a relative absence of fat. It appears that the apparent plasticity and adaptability of fat exceeds the anatomical convention that unifies organs into objects with a clearly discernible boundary, structure and function. The reclassification of fat as an organ thus challenges the certainty of anatomy’s bounded forms.

Further, the act of reclassifying fat as an organ raises questions about the ways in which fat was previously perceived. For if we consider it a given that the anatomical body is made up of organs, how then did this formerly considered ‘non-organ’ of the body exist in an environment in which it was seen to operate as an almost, but not quite yet, accepted part of the anatomical body? Complicating the situation even further is the recent finding that fat contains significantly higher pluripotent stem cell yields than bone marrow2. These adipose-derived stem cells can be differentiated towards adipogenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic, myogenic and neurogenic lineages, i.e. to grow fat, bone, cartilage, muscle and neuronal cells, which means that fat has gone from its position as a non- organ, to that of an organ, to now being an organ that has the capacity to make all other organs (i.e. ADSCs have the potential to become any of the body’s cells). In a sense, we are witnessing fat’s transgression of the boundaries that work to define our understanding of anatomy. Indeed, the capacity of fat to go beyond – to test, trouble and deeply complicate – the paradigms of anatomy, remains a relatively underappreciated quality of this organ.

Nina Sellars is an artist who works across the disciplines of art, science, and humanities. Currently, Sellars is Artist in Residence at SymbioticA, The University of Western Australia – for the research and development of tissue culture techniques for her arts project – Fat Culture. This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

References:

- Rosi Braidotti, _The Posthuman_ (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013), 136↩

- Sahil K. Kapur and Adam J. Katz, “Multipotential Aspects of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells and Their Spheroids,” in Stem Cells in _Aesthetic Procedures: Art Science, and Critical Techniques_, ed. Franco Bassetto, Alberto Di Giuseppe and Melvin A. Shiffman (Berlin: Springer, 2014), 181.↩