Vocabulary of Plants and other activities or my take on human (de)centred environmental data

Kasia Molga

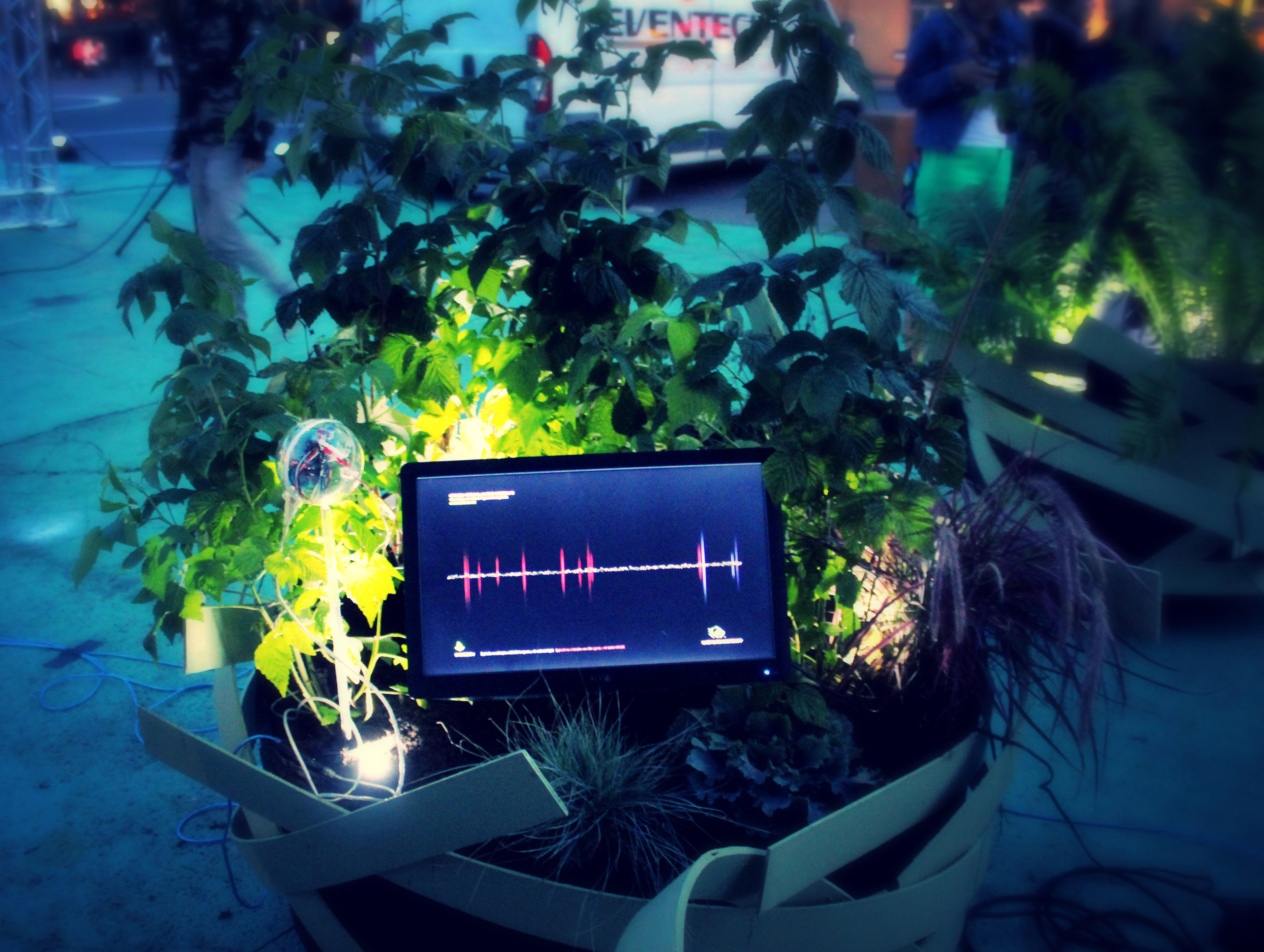

Image: World Wilder Lab

Once upon a time a lot of our actions – whether in cities or rural places - were governed by myths and beliefs where the power and mercy of natural forces could reward us or wiped us off the surface of the planet. We have feared and respected elements and felt very much interdependent and interconnected with it all. Now, especially in the so called “developed world” and its big cities, with the fast progress of scientific research and emergence of new technological advances we gained a lot of knowledge but lost most of those beliefs. And so perhaps one of the reasons why we are now facing problems of climate change and decreasing biodiversity is because of the lack of powerful narrative about us being an integral part of “nature”.

It is in particular present in architecture and urban planning – building walls and boundaries, which divide us from wilderness. Often when city dwellers talk about “nature” – that “nature” is something outside our cities – i.e. we go to “nature” to rest and play. But in fact “nature” is very much present everywhere. There are plants, microbes, insects, animals and us co-habiting in our towns, just that everything, except us – humans – is regarded as a backdrop, decoration or nuisance. But every living organism is a vital part of our urban environments and environmental health. And so are entities and processes which we take for granted, but which are basic to sustain this very delicate layer within which the rich life can flourish.

A lot of things constituting this particular layer called “life” on our planet can be now detected, recorded, analysed and quantified thanks to the aforementioned scientific and technological progress. So while data sets have abolished myths and beliefs, tools such as the microscope for example, enabled us to see real wonders – existence of which we could not possibly dream about before. But there is something else which might have been abolished too – that is our emotional relationship to those wonders. Did knowledge neutralize our feelings – fear, awe, love, passion, sadness – towards natural elements, because now we can conquer them? And if yes – how can we even start to care about nature and environment if we do not have any emotional connection to so many other species and entities – fellow Earthlings - inhabiting this planet?

In my practice I am fascinated with data. Since the advent of IoT – the concept, technologies and network, I started exploring real time environmental signals not for the purpose of storing, analyzing and using them as the information to our advantage, but as the language of the source of these signals (biosemiotics) – be it an air quality, processes in soil or voices of tiny microbes. These signals – that data – make things undetectable and invisible – present and noticeable. Thanks to it we can observe the world – especially its virtual image in much higher definition.

The data for me – scientific, true and unbiased, is a starting point of a tale – a story told by something other than a human. It is my attempt to get us out of our “umwelt” and see beyond our egocentric selves; and provoke and evoke emotional reactions to animals, microorganisms, processes, chemical reactions etc. which are in such mode of being that we do not pay any attention to them, but which are crucial to keep the equilibrium.

For example in World Wilder Lab’ PlanEt project we aim to look at plants as a collaborators and designers in creation of our future cities. By acquiring and understanding signals from plants we hope to change people’s attitudes towards plants, so that their role in our sustainability is recognized and respected and so that their “voices” are heard and so that we can learn from them. We want to create a community of PlanEt’s users (by releasing it as open source/hardware device) and that way engage people to build their own PlanEt devices and to read and share data from plants. This community will help to compile a very first Vocabulary of Plants, which hopefully will change city dwellers perception on the role of plants in our environment; and help in answering questions about how we can apply data from plants to better urban well-being, horticulture / urban farming or to tackle local warming, pollution offset, noise reduction or just residents mental health issue.

Image: World Wilder Lab

In another work –The “Human Sensor” I wanted to know whether I could learn something about my surroundings from the quality of my own breathing. I was curious what real time data coming from my own exhaled breath (that is from my inner environment of my own body – or as I call it “invironment”) could tell me about the air quality which inevitably we must inhale. The “Human Sensor” initiated my inquiry by taking an advantage of my existing illness. The exhaled breath from people who suffer from Asthma and COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) is marked by the presence of higher level eNO (exhaled Nitric Oxide), which then becomes a parameter dictating how the data will be manifested. Thus eNO distinguishes those we consider as suffering from COPD & Asthma as ‘Human Sensors’, capable of registering changes in the quality of air. In the “Human Sensor” I look at the frequency and density of chemical compounds and particulates in the air and the breath, transmitted and recorded using various sensory technologies embedded in a wearable. Then I translate and interpret that data to render the invisible fragments of the air and atmosphere to be manifested and intensified. That data from the normally unnoticed, quiet and very private action of breathing can be considered as set of signals informing me about my relation to that system. And so the “Human Sensor” becomes a narrative about the air quality written by ephemeral and intimate breathing, where data is a proof of a deep interconnection between “inner” and “outer” – and our own vulnerability.

Image: The Human Sensor

Lastly in Coral Love Story I wonder whether we can start caring about the species which not only that they live in totally different side of the planet, they also live in a very different habitat. The whole project very much depends on IoT concept and its application – distributed all over various scientific stations sensors which gather data about corals’ and reefs conditions. Corals itself are environmental sensors informing us about the quality of our oceans. Coral Love Story is a number of interventions enclosed, just like a regular book or story, in chapters. Through using data I want us to fall in love with these tiny creatures, empathise with them and start thinking outside our own “umwelt”, hopefully changing some of our harmful behaviors. Chapter #1 is a design fiction - a haptic wearable – a second skin – which by vibrations, and color changing patterns, informs the wearer and people around her, about the coral bleaching event happening right now in the Great Coral Reef. The vibration can cause pain and discomfort, the color disappear making this piece transparent. If we could wear something like that on everyday basis – would we feel more connected to other species of this planet?

Images: Coral Love Story

It is clear that this whole “data” concept opens up a lot of possibility. But it also has overwhelmed with us information (according to Erik Schmidt every two days we create as much information as we did from the dawn of civilisation up until 2003, approaching five exabytes), and in the mainstream domain it seems to be very narrowly human centered. The main rhetoric is about how it can help business to make money and how we can control our personal pieces of information. Obviously those are very important subjects, but isn’t this view of data very limiting? I hope that my peers and I are helping shift this conception and start revealing data’s poetry – rendering visible the invisible “mesh” – as defined by Tim Morton - which holds us (by ‘us’ I mean humans and all other living and non-living beings) all together; evoking empathy and partnership with nature; and enabling us to listen to new stories – not myths or tales – but real life stories – creating an opportunity for a fresh exchange with the living cosmos.