Open

Collaborative

Making

A digital perspective. As part of V&A Digital Design Weekend 2014

AHRC

Andrew Prescott

Re-making the Humanities

Computers developed from the wish to expedite the mundane, to complete repetitive, boring tasks more quickly and accurately. Charles Babbage dreamed of a ‘difference engine’ because he thought that machines would make a better job of calculating and printing mathematical tables than humans. Humanities scholars began using computers when a catholic priest, Roberto Busa, struggled to create an index of the works of Thomas Aquinas and wondered if IBM could help. Our engagement with computers is now moving beyond such utilitarian beginnings, and we can more easily appreciate how the poet Richard Brautigan could view computers as ‘machines of loving grace’ and ‘flowers with spinning blossoms’.

The electronic records of President George W. Bush deposited in his Presidential Library comprise over 80 terabytes of data (to give an idea of scale, all the printed books in the Library of Congress represent about 50 terabytes of data.) The e-mail archive of the Bush administration contains over 200 million e-mails. In order for historians to analyse 200 million e-mails, they need new tools, skills and methods - possibly even a new historical imagination. Simply reading or searching is not powerful enough to understand and interpret so many messages; we need to mine, link, visualise and quantify. Moreover, old-fashioned books and articles are not a good way to describe scholarly explorations of such huge data resources. Instead, we need scholarship that is more data-driven, visual and interactive. Researching an archive like that of President Bush will be a visual, haptic, and interactive process, so that writing history becomes more like playing a video game. We are used to the results of historical or literary research being presented in textual form, but the rise of large data sets and quantitative methods mean that increasingly, humanities researchers require a strong visual and design sense.

The ways in which arts and humanities researchers are engaging with new technologies are the focus of research funded by the Digital Transformations theme of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC.) The AHRC is a government body sponsored, like other members of Research Councils UK, by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. The AHRC funds and facilitates research into the arts and humanities, and each year uses approximately £98 million of public funds to provide some 700 research awards, 2,000 postgraduate scholarships, and numerous Knowledge Transfer Awards. Digital Transformations is one of four current AHRC strategic themes. Projects funded by the Digital Transformations theme explore how engagement with digital methods is changing the aims, practice and dissemination of research in the arts and humanities. They also provide arts and humanities perspectives on major social and cultural questions posed by digital technologies in areas such as identity, intellectual property and cyber security.

Work undertaken through the Digital Transformations theme ranges from investigations of changing patterns of reading and publishing through to visualisations of translations of Shakespeare. The various approaches encompassed by the theme are re ected by its three largest projects. links data from criminal trials held at the Old Bailey in London with data concerning the settlement of Australia in order to explore the lives of over 66,000 people sentenced at the Old Bailey between 1780 and 1875, and shows how techniques of linking datasets and data visualisations can transform historical research. The second large project,

, will use automated processing of images and crowdsourcing to increase dramatically the scale and speed with which archaeologists can investigate large sites and whole landscapes. Finally, ‘Transforming Musicology’ (www.transforming-musicology.org) examines how our ability to automatically process and manipulate music changes our approach to the study of (for example) lute music or Wagner’s operas.

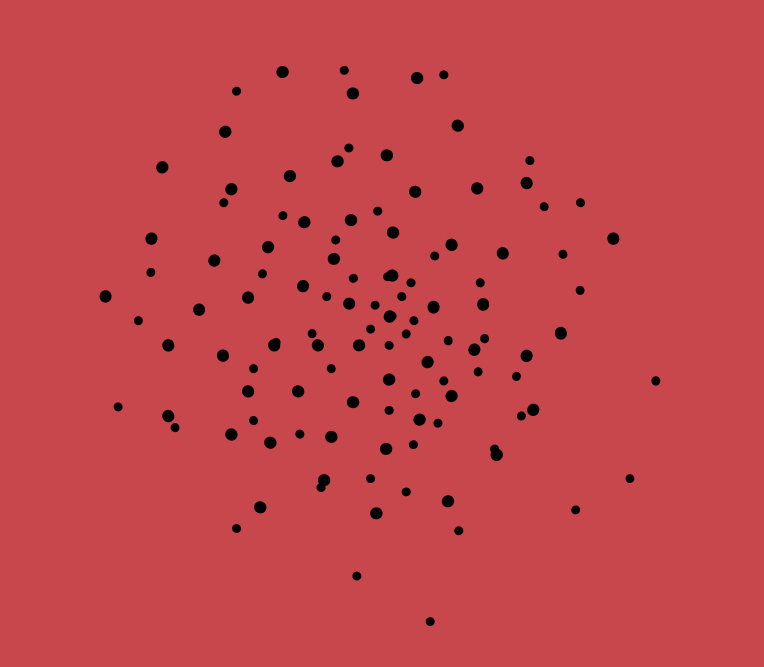

A fundamental component of digital transformation is the way in which familiar cultural categorisations of form are being eroded. Images, texts, music, film and artefacts are now represented and distributed in digital form, and can be mixed and mashed. This merging of cultural forms challenges the intellectual silos of academic disciplines. Digital scholarship is inherently interdisciplinary and offers humanities scholars and artists new opportunities for collaboration. Design will be an important meeting ground, as can be seen from an AHRC funded project at the University of Glasgow, . The linguistic comparisons by which we describe ideas and feelings contain much cultural information. By tracing how metaphors change through history, we can create an archaeology of past mentalities. The ‘Mapping Metaphor’ project uses the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary to create visualisations of the historical development of human ideas and associations, showing how design can help represent knowledge.

When work began on the Digital Transformations theme it seemed data was becoming an evanescent quicksilver medium living in an ethereal cloud. But digital transformations always wrong-foot you, and we have recently become more aware of how the digital can become material. Digital materialities are another area where design provides a meeting ground between arts and humanities. Some AHRC projects are exploring how the ‘Internet of Things’ will reshape cultural engagement. For example, ‘Tangible Memories’ (www.tangible-memories.com) at the University of Bristol seeks to develop a sense of community and shared experience for residents in care homes by co-operative exploration of their life stories. The project will attach stories to objects that are personally meaningful to participants so that they can remind themselves of important memories and share them with others.

A fascinating expression of digital materiality is the conductive ink produced by companies such as Bare Conductive. Conductive inks enable circuits to be drawn or painted, and drawings and paintings to become circuits. We have assumed that ‘analogue’ and ‘digital’ are antithetical, but conductive ink changes that. A silkscreen print can become digital and interactive, as the YouTube video of Eduardo Kac’s beguiling ‘Lagoglyphic Sound System’ (2012) illustrates. Jon Rogers, Mike Shorter and others at the Product Research Studio have shown how conductive ink transforms paper into a flexible platform for digital products of all kinds, such as paper headphones.

One of the most exciting activities I have undertaken as part of the AHRC Digital Transformations theme was the presentation at the Cheltenham Science Festival of ‘Contours’, an interactive sound sculpture using conductive ink by Fabio Lattanzi Antinori with Bare Conductive and Alicja Pytlewska. (Fabio is presenting ‘Data Flags’, another work using conductive ink, at the V&A during the Digital Design Weekend.)

‘Contours’ is a metaphor for the idea of breathing life into a textile skin, and consists of interactive tapestries with capacitive sensors using conductive ink. As visitors touch the tapestries, they modulate a data-driven ambient soundscape reminiscent of a medical research environment. In ‘Contours’, Fabio uses new materials to connect science, art and the humanities. This approach encapsulates the spirit animating the AHRC’s work on Digital Transformations.

Andrew Prescott, AHRC Digital Transformations Theme Leader Fellow, King’s College London.

Data Objects: Turning Data into Form

For many people outside the scientific community statistical information, spreadsheets and graphs remain abstract and difficult to comprehend. This research investigates how we might interpret complex technical/digital information through the creation of physical objects, designed with the intention of bringing better understanding and increased accessibility to scientific data for a variety of non-specialist audiences.

In an AHRC funded pilot study, data gathered on the varying abilities of older people to open ordinary domestic jar lids was used to design a number of physical data- objects that represented this data in different ways. Some objects were created by hand by artists/designers and others were created using computer-based modelling and 3D printing technologies. A range of people with different interests in the data were asked to interact with the objects and discuss which objects they thought helped to communicate and add insight to the original information.

From the outset we have been interested in how a fusing of digital/material practices, attributes and qualities could be used to explore not just new concepts for digital technologies such as 3D digital printing and data visualisation, but also the creation of hybrid constructs that borrow from the languages and conventions of both digital and material cultures, and how these hybrid constructs might begin to bring about shifts in expectations of the relationship between digital and material paradigms and the ways in which these paradigms might work together.

The research also investigates how we might begin to use these constructs to communicate information, ideas and concepts, taking into consideration the operational and experiential expectations inherent in both digital and material environments and artefacts. This allows for our interaction with digital data to move beyond the confines of the computer screen into a located physical experience, enriching the potential for the translation of knowledge.

However, the actualising of a digital data-set into a physical object may initially seem paradoxical, since by xing digital data in time and physical space we would appear to disable much of the dynamic potential inherent in computer technologies. One of the aims of this research was to question if these ‘concertised’ data-sets might retain echoes of their digital origins and capabilities such as dynamism, complexity, interconnectivity, mutability and so on, and to examine if by creating a data-object we can begin to describe a set of possible relationships between the digital traits described above and the material properties inherent in the physical object, such as tactility and notions of uniqueness, preciousness, durability, history and value, in both economic and socio-cultural terms.

Ian Gwilt, Professor in Design and Visual Communication, The Art and Design Research Centre, Shef eld Hallam University.

The Secret Life of a Weather Datum

Putting ‘big’ weather data in the spotlight, ‘The Secret Life of a Weather Datum’ project seeks to develop a new approach for understanding and communicating how socio-cultural values and practices are articulated in the transformation of weather data on its journey from production through to various contexts of ‘big data’ collation, distribution and re-use.

The team are following a single temperature datum produced at the Weston Park Weather Station in Sheffield. The station is one of the oldest weather stations in the UK and is one that has made a significant contribution to the climatic record. The team are following this datum on its journey through the Met Office, through the governance structures which shape its journey, and on into two cases of re-use: climate science and financial markets. They are also exploring the datum’s intersection with data produced by amateur observers, including their own weather station built using a Raspberry Pi, and citizen scientists involved in transcribing old weather records that have been recovered and rescued from archives. At various stages of the datum’s journey the team are collecting interview, observational, photographic, digital ethnographic and documentary data relating to the socio-cultural values and practices shaping the use and journey of the datum, and analysing these in relation to the broader social context.

From this research an interactive website and research data archive is being developed that allows users to follow the journey of the weather datum and explore the socio-cultural values uncovered at various stages on this journey. A visualisation of the journey is currently being developed that resembles a map similar to that of the London Underground. Each station on the map will represent an organisation, project or institution that the weather datum travels through, and users will be able to enter the stations to explore the socio-cultural values and practices uncovered by the research team in that location. The tracks on the map connect each station, and offer a visualisation of the flows of data between stations. This method of animating the research findings further develops the concept of ‘following the datum’ beyond being solely an approach to guide data collection into a design-orientated process of documenting and preserving the motions and actions of the weather data as it moves through different spaces.

Project Team: Jo Bates and Paula Goodale (University of Shef eld), Yuwei Lin (University of the Creative Arts.)

The ACCORD Project: Co-producing our digital heritage

The ACCORD project is actively researching the opportunities and implications of digitally modelling heritage places and objects with communities. Central to ACCORD is the notion that the growing accessibility and ubiquity of digital technology means that heritage can increasingly be created and recorded by everyone. The project’s answer to the question ‘what is heritage?’ is entirely community de ned, from rock art to rock-climbing, and we encourage the participation of diverse groups across Scotland. Working with visualisation technologists and community engagement experts, community groups design and produce 3D models of heritage places significant to them using techniques such as photogrammetry and Reflectance Transformation Imaging. The results are then permanently archived so that they are freely reusable by all. This process raises fascinating questions surrounding co-production, value and the experience of authenticity in relation to these new heritage records.

There have been over two decades of research and development of digital visualisation technologies in archaeology and heritage. Approaches that utilise photogrammetry, laser scanning and 3D modelling have become standard practice in academic archaeology, commercial archaeological ventures and cultural heritage management. However, there is as yet little community engagement with digital visualisation technologies, despite community interest in the technologies themselves. Expert forms of knowledge and professional priorities, rather than community ones, invariably inform digital visualisations and the results, when seen from the outside, can seem disconnected, clinical, and irrelevant. Low levels of community use and re-use, let alone co-production, of these resources highlight concerns relating to perceptions of authenticity and value. The ACCORD project challenges this status quo and explores issues surrounding expertise, ownership and value in digital heritage visualisation through co-design and co-production. Importantly, forms of community-based social value relating to the historic environment are integrated into the design and recording process. Funded by the AHRC Digital Transformations programme as a Connected Communities project, ACCORD is a 15-month partnership between the Digital Design Studio at the Glasgow School of Art, Archaeology Scotland, the University of Manchester and the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.

Project Team: PI Stuart Jeffrey, CI Sian Jones, RA Mhairi Maxwell, CI Alex Hale, Phil Richardson and Cara Jones.

Our Data Ourselves

Do you know how much data you generate? Do you know where it goes? Is it being sold by Google to increase their market share, now valued at £250 billion? Is it being ‘scooped’ by the GCHQ or NSA? The Snowden revelations show that security agencies are surreptitiously taking data from our phones, cameras, apps, and anything else that leaves a digital trace. Especially if you use a mobile device, you are actively contributing to the 2.5 billion gigabytes of data generated daily. To put that in perspective, this would be enough data to fill one hundred million iPhones, every day. Yet public understanding of our information-rich environment and our quantified selves remains underdeveloped.

‘Our Data Ourselves’ is a research project at King’s College London examining the data we generate on our mobile devices. We have brought together media and cultural theorists, computer scientists, programmers and youth to explore this ‘big social data’ (BSD) we generate. As arts and humanities researchers we are interested in the development and transfer of the technical skills and knowledge necessary for the capture and analysis of the different forms of BSD, and its transformation into community research data. Our project asks whether BSD can be transformed into a public asset and become a creative resource for cultural and economic community development.

Herein lies a fundamental challenge with big social data. Even though we generate this data, it does not really belong to us. The moment we upload content, interact with a website and/or use an app, data flows out of our devices into myriad complex circuits where it is aggregated, that is, cut up, mixed, matched, and endlessly recombined with other data. Once recombined to produce value, it is returned to us in everything from targeted ads to security flags. As worrying, this all transpires in a highly proprietary environment, leaving us in a data-centric society over which we have little control and limited understanding.

A first step in critical inquiry comes in the moment of data generation. We are developing apps and tools that will trace, extract and visualise the data that gets generated by youth. We have paired with members of Young Rewired State, a UK-based independent global network of young people under 18 who have taught themselves to programme computers, code software and share their ideas with like-minded peers at events around the world. Our co-researchers are working with us to develop tools and applications to capture, visualise and understand key components of that big social data, specifically what is generated when they text, browse, post, and generate symbolic content on their smartphones.

We have already held one hackathon where our youth coder partners considered the ways in which smartphones generate BSD. The questions that they focussed on allowed groups to improve upon the MobileMiner app that we have developed to track the data they are generating on their devices; to think about how privacy agreements increase dataveillance; and finally to consider the access to personal data that third parties are granted, particularly via seemingly benign smartphone applications. We will hold another hackathon that will explore both tools for analysing data captured on personal devices and the development of an ethical framework for data sharing available for widespread community use. It is our contention that in creating an open environment for BSD research and developing an ethical framework for data sharing available for widespread community use, we can contribute to a big social data commons. Indeed, if it is ‘our data ourselves’, our BSD commons will empower us to use it in new ways, both in community and by arts and humanities researchers.

Project Team: Tobias Blanke, Mark Coté, Jennifer Pybus and Giles Greenway.

Poetics of the Archive: Creative and Community Engagement with the Bloodaxe Archive

The Bloodaxe archive, newly acquired by Newcastle University, is an internationally significant resource for contemporary poetry and includes files of poems, with editorial markings, letters and financial information relating to all the poets Bloodaxe Books has published since its inception in 1978. The challenge of this project, funded by the AHRC, is not only to make the resource available for scholarly research through creating a standard web-based catalogue, but also to reframe the archive by designing more creative, open-ended and playful interactions. The project brings together a multidisciplinary team of poets, literary researchers, visual artists, digital artists, data visualisation specialists, filmmakers, archivists and library staff. In addition, the project introduces different community groups of poets, poetry readers and young people to the physical archive with a view to allowing their active engagements to animate and expand the meaning of the space between user and archive, to feed into the design of new interfaces and to drive the development of new theoretical and critical questions about the nature and use of literary archives.

The project will add material to the archive through filmed, in-depth interviews by Colette Bryce and Ahren Warner with poets published by Bloodaxe Books. Some of these have already been collected and edited into a film, ‘Conversation for an Archive’ recently shown at Poetry International at the Southbank. New visual materials, mash-ups, texts, films, hybrid forms and installations are in process of development. Using digitisations of materials in the archive, cleared in terms of copyright, the project will also produce a ‘generous’ exploratory interface that will enable multiple forms of visualisation, aggregation and comparison of archive content.

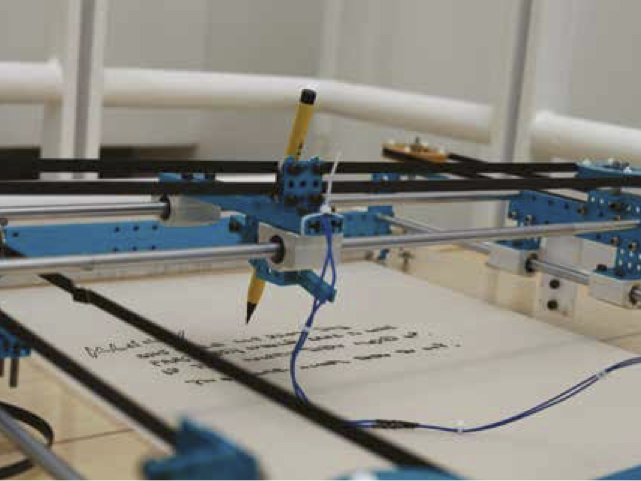

One idea being explored, for instance, is a novel kind of search and comparison between the shape and line length of poems on the page. Technology, far from offering a simple antithesis to the paper archive, can, we believe, liberate us to think about both the mobile process of writing and editing and the materiality of paper, in a kind of future retrospective. The ‘Marginalia Machine’ for instance, designed by Tom Schofield, separates the marginal notes on the paper from the background text as they are digitised and reproduces them in a public performance of writing on a continuous paper scroll. This puts the fixity of archived papers back into movement and provokes re ection on conventional thinking about what is lost in digital reproductions of the archived page. Other digital visual materials approach the intimacy of paper, “the simple, strokeable, in the handness of it” as Anne Stevenson writes in a poem entitled simply ‘Paper’, and our fascination with the word, particularly the hand-written word, inscribed or traced on it.

Project Team: PI Linda Anderson, RA Colette Bryce, RA Ahren Warner, RA Tom Schofield, Rebecca Bradley, Kimberley Gaiger, CI David Kirk, CI Irene Brown, CI Alan Turnbull, CI Bill Herbert, CI Jackie Kay CI Sean O’Brien and filmmaker Kate Sweeney.