Open

Collaborative

Making

A digital perspective. As part of V&A Digital Design Weekend 2014

Uniform

Martin Skelly — Jon Rogers

Design and designers have always played with and shaped the world around them. Charles and Ray Eames showed the world just how agile, flexible and relevant design is across every part of our lives: from what we sit on, to how we learn, to what technology can do, to how we understand the vastness of the universe and the minuteness of the cells in our body. Their activity spanned a world in change in the post world war II era. They understood global change. And they understood design for global change.

Once again, we’re in an era of unprecedented change and evolution. And we know that there has never been a time where creativity and design could be more influential and more important. If we consider how the digital revolution is changing the world from a push to a pull economy, and in turn our relationship with how data is created, shared and understood, then the case for design is potentially staggering. It provides us with exciting opportunities for creatives to start to shape this new world through considered creative practice. It provides a whole new playground for what designers can do in the digital world. With this in mind, we’d like to share two projects that in different ways start to show what we believe is the future landscape where creativity, technology and innovation collide, and where agencies like Uniform play a role in imagining the future.

In our everyday work, and more speci cally through our R&D platform, we are constantly looking at what the future looks like, and in this case exploring new ways of connecting brands with consumers. Martin Skelly, Creative Technologist, talks to Prof Jon Rogers at the University of Dundee, to explore how we can bring the physical web closer to the clients we work with.

Nick Howe, Uniform.

Can light call us to Twitter?

Jon — “The pioneer of Design Thinking, Tim Brown, says many clever things. One of the cleverest is: “Thomas Edison created the electric light bulb and then wrapped an entire industry around it. Edison understood that the bulb was little more than a parlour trick without a system of electric power generation and transmission to make it truly useful. So he created that, too.” What’s not to be marvelled at with the creation of artificial light? The beauty and powerful magic of a light draws us in. What must it have been like to see electric light for the first time? We are now facing a similar revolution in what a light bulb could be. What happens when a light bulb is connected to the Internet? As soon as it does, it changes from a light to a pixel. It follows that if we are controlling a light with a computer then it becomes a pixel that we can write behaviours to. Which means that we can harness light’s ability to connect us to new things. If we can do this, can we connect a light to the Internet and then have a pixel that responds to social media? Can a light call us to Twitter?

What meaning can we take from a twitter-connected pixel?

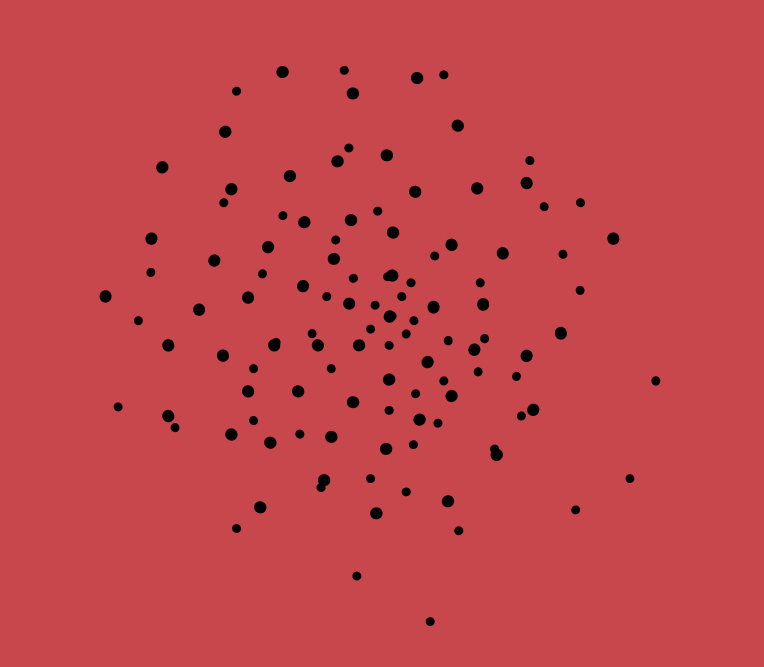

Martin — “One thing I’ve been thinking about is how would it feel to glance into a data cable that is powering a Twitter conversation? What could each of these tweets zapping around cyberspace actually look like? I also wanted to explore a sector that Uniform already completes a lot of work in – sport. We already work with The FA and Liverpool Football Club. I wanted to combine match day excitement with ‘Internet of Things’ geekery. Football grounds have a completely unique atmosphere on match days, but for days before and after matches, the beautiful game is the topic of millions of individual contributors on social media. We wanted to explore these colossal metrics, to visualise the social media buzz in between matches. It’s a bit like standing outside a stadium on match day – hearing the chants, and the near misses, and the goals - but you are staring into the depths of an online conversation instead.

A large number of people discussing a certain subject or theme can act as an early warning indicator of immediate, big news. We’ve called the project Kixl, a mash up of kick, and pixel. Kixl is a physical object that visualises the number of tweets on a certain hashtag with simple colour changes. At its simplest, Kixl is a glanceable object that tells us the state of a specific conversation on Twitter, the same way that we use a clock as our visual check-in with time.

What are your thoughts on the meaning that physical pixels can provide?

Jon — “Think about it. A light bulb. All pervasive and everywhere. Could they subtly inform us that our morning bus is delayed? Could they excite us that our bid on Ebay is approaching a crunch point? Could they relax us that granny’s gone to bed safely? What would you want a light to be if it was a pixel? The meaning really is extraordinarily broad, scalable and writeable in any direction. And as creative technologists, it’s a great space to play in.”

And now for the techie bit. How did you bring it to life?

Martin — “I began by using an Arduino and some high voltage RGB LED strips to experiment with light behaviours and get the colour balances right. For a design as simple as Kixl, it’s important that each part looks amazing. So before touching Twitter or hooking the device up to the web, I explored the design of the casing and the layout of the LEDs with dummy data. I needed maximum daylight brightness but a wide viewing angle to allow groups of people to be able to glance at the device. When I was happy with the design, I started exploring methods for getting it connected to the Internet. Arduino Ethernet shields are my go to treatment as they are extremely reliable, but can be clunky when taking it out to client meetings.

Calling ahead or hoping that they will have wired Ethernet isn’t ideal, so we ruled this out. When we started exploring wi- , we knew that building the one-off prototype would be relatively cost effective with Arduino. However we knew from previous projects that unit costs and development time would spiral if we wanted to scale the project up in the future.”

You thought that this was a perfect project for playing with the Electric Imp. Why?

Jon — “What I love about the Imp is that it provides a prototyping platform that is a direct link to a marketable product. Which means that although you can treat it as prototyping platform for playing with ideas, you can also use it as a delivery platform if one of those ideas starts to head down a potential mass-market route. I love Arduino. It’s amazing. But one of the limitations is that it’s very hard to go from an experience prototype or concept model to anything more than a one-off. There is no data model behind it. There is no direct way of connecting it to the web and providing a web-service to power it. There is a very long runway between concept and product. With the Imp that runway is very short; they have the business models in place to enable you to have a data-enabled product connecting to the web. They have the supply chains in place to make that happen if you want to release a product. That is a very seductive proposition. But actually, that’s just half of the story.

What I love is the technical platform. How shall I say this in a simple way? It’s basically a platform that is super easy to connect an object (let’s say a light) and have its behaviour controlled over the web. It’s super easy to create a pixel from an LED (or collection of LEDs) that is both programmable (you program the Imp to dim the LED over the web and it dims the LED, over the web.) But that’s not all. You can also have it connect to another cloud-based server that allows the web to control the light, over the web. You can do a whole load of cloud-based heavy-duty processing that then talks to the light over the web and does complex and beautiful things.

The Making of Weather Systems

Weather, the ‘Internet of Things’, Micronetworks and Utopian Socialism.

Recently, we’ve been exploring some of the different hardware platforms that are enabling the creation of connected devices and spearheading the development of the ‘Internet of Things’. We aim to make devices that are easy to understand, practical and enjoyable to use, and we wanted to explore how we could extend the network of designers, researchers and craftspeople we work with to develop our ideas into demonstrators and ultimately products. With all that in mind we decided to work with Studio PSK to develop a series of connected devices that could provide localised real time weather forecasts, powered by BergCloud. It’s commonly held belief that the British are preoccupied by the weather and according to research, 70% of the UK population check the weather forecast at least once a day. The popularity of weather app downloads around the world illustrate that the weather is a global common denominator, and reports indicate that checking the weather is the most frequent activity of smart phone users and one of the first things that we do in the morning. The challenge for us was whether a connected device could improve on this experience by taking the data off the screen and translating it into physical behaviours. In particular we were keen to think about how the objects could express some of the whimsy and playfulness we associate with the British obsession with weather whilst maintaining a visual aesthetic that suggested scientific rigour, accuracy and trust.

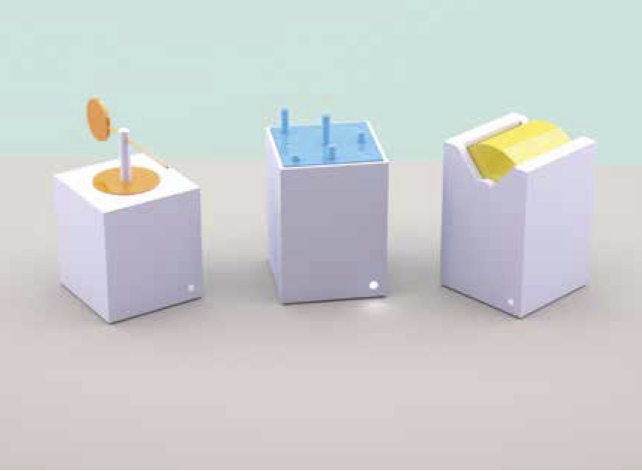

There are three devices that forecast rainfall, temperature and wind. One aspect of the devices that got us particularly excited was the ability to use existing APIs and weather data to accurately forecast the next 10 minutes of weather and provide extreme weather alerts. The design of the apps was a collaboration between Uniform and Studio PSK. In the case of the Rain device, both were keen to simulate the sound of rain through a mechanical system, Pete Explains:

“We looked at loads of different options, things like rain sticks and the drums they use to make rain sound effects for radio, but we couldn’t get the sound right. In the end we settled for something a little more abstract, but visually engaging.”

The pins that pop out from the top of the Rain System are meant to resemble rain splashing up from a puddle. The ‘puddle’ is a thin metal plate. When a rain alert is detected a grid of solenoids activates the pins. Each solenoid pushes a pin against the plate creating a sound. Collectively it illustrates the intensity of the imminent rain.

The design of the temperature System drew inspiration from the silent monitors used by Robert Owen, a utopian social reformer of the 1800s. Silent monitors were used to enforce discipline without recourse to violence at the New Lanark Mills in Scotland. Pete explains the connection:

“I’d seen these monitors years ago and they were lodged in the back of my mind as being a really good example of glanceable communication. They typify the simple behaviours we associate with connected devices that are used by multiple people in shared spaces. The Silent Monitor was a small wooden block with 4 coloured faces. Each face could be used to describe the behaviour of the mill workers with each colour representing a different type of behaviour ranging from Excellent to Bad. In the same way, our System uses 4 colours to convey at a glance what the ‘feels like’ temperature will be ranging from: ‘Below 5 degrees’ to ‘Over 20 degrees’. It’s the simple kind of information that might dictate whether you choose to wear shorts, grab a coat or wrap up with scarf and gloves.”