Noisy Chatterbots

Dr Libby Heaney

The term ‘Chatterbot’ was coined in 1994 by Michael Maudlin to describe an artificial intelligence system that converses with users via text. Now known as chatbots, such speech or text dialogue systems are commonly used as voice assistants or perform routine tasks for call centres. Although in the research community the term ‘chat’ has evolved to mean non-goal directed realistic conversations, like how you might talk to your friends at a party1.

Chatbots are defined by their limitations to hold flexible conversations and have no real understanding of the language they use.

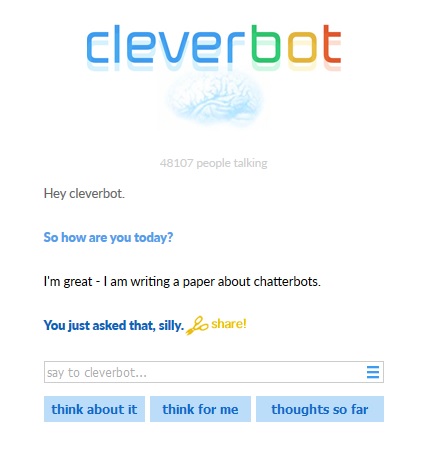

Google Duplex, which works well in online demos, is rigid, being trained for a narrow set of specialist conversations such as booking a table at a restaurant. And while the conversations with popular online or app-based chatbots like Cleverbot or Replika are non-directed and make grammatical sense, the level of conversation is superficial.

Dialogue from www.cleverbot.com

Dialogue from www.cleverbot.com

In my own artistic research, I have tested deep learning chatbots deployed over the web. In doing so, I have noticed a trade-off between accuracy of a chatbots response and the time it takes before a chatbot replies to a user. In other words, it takes a non-insignificant amount of time for a deep learning chatbot to respond with a grammatically correct statement, which in itself occurs probabilistically. The delay and apparent randomness in meaning and grammar make it challenging to keep people, who are used to instant, easily understandable information, engaged. As an artist, I am very interested in the limitations of machine chat as a creative medium. More about my work later.

The word chatter originated in the 13th century to mean a run of quick shrill sounds, initially of birds. Today, in the context of everyday conversations, chatter refers to rapid and foolish talk or a succession of quick, inarticulate speechlike sounds. On the other hand, the etymology of the word chat, derived from chatter in the 1500s is familiar conversation. So while the AI research community strive for familiar conversations, I am interested in reassessing the term chatterbot. That is, systems where ‘foolish talk’ lacking forethought or caution is embraced and ‘inarticulate speechlike sounds’ create context free, free associations, that is unconscious thoughts and feelings in the users.

Le Guin wrote “One of the functions of art, is to give people the words to know their own experience… Storytelling is a tool for knowing who we are and what we want”2. So how can chatterbots be designed to reimagine and reinterpret existing stories, allowing us to gain new insights and knowledge about the world and our place in it? In these unsettling times, how can human interactions with chatterbots create a dada-esque poetry gleaned from the rules of algorithmic systems and fragmented data?

To design such chatterbots, the training set (the text that the machine learning system produces its language model from) should be not too large. Otherwise the conversation may end up highly predictable and too close to reality. Likewise, the training set be should not too small. Otherwise the chatterbot will get stuck on one or two responses. It is the noise in the training set that enables new experimental stories to emerge. In other words, the quality and quantity of the data in training set, alters the chatterbot’s ability to build up previously unspoken and unpredictable rapid and foolish talk.

Chatterbots critique the machine learning approaches of the big four tech companies. These companies hold vast amounts of text, image and audio data largely about us, collected by their free software tools and apps. Patterns found in this data mimic current structural biases. For instance, research has shown that standard language training sets, such as back issues of the Wall Street Journal, use only standard english and leave out whole segments of society who use dialects and non-standard varieties of English. Another example, discussed by Caliskan et al3, demonstrates how machines that learn word associations from written texts, also mirror the associations learned by humans (this is not surprising!). These associations were measured by the implicit association test, which uncovers associations between concepts, such as pleasantness and flowers and unpleasantness and insects. The test also revealed the machines learned unconscious biases in our attitudes and beliefs, for example correlations between female names and family and male names and careers.

These correlations are strong signals in the data set as they occur frequently in the recorded totality of our conversations and correspondances. They therefore appear as highly likely outputs in dialogue systems. However, if the data set is noisy or gradually contaminated with another source, these biased strong signals become increasingly washed out and other relations may take their place instead.

The concept of apophenia helps us to understand the consequences of blurring the signal and noise. Apophenia is the perception of patterns within random data, like when we see faces or objects in clouds. Machines sense patterns in our data that humans cannot spot and that might otherwise be designated by us as noise (as opposed to the signal). Steyerl, in her e-flux article A sea of data, highlights the deadly politics of machine learning systems. She describes how Pakistani civilians were wrongly identified as terrorists by NSAs Skynet algorithms and killed in drone strikes on the basis of limited data and over fitting (looking too hard for signals in noise) by the algorithms.

Therefore when designing chatterbots to reimagine narratives, as opposed to reflecting existing views and biases back at us, it is important to train the system not produce an analysis of an input that corresponds too closely to dominant narratives or contexts. Otherwise, the user will remain in the echo-chamber of their own thoughts and opinion, with sometimes dangerous consequences.

I believe chatterbots have the potential to disrupt embedded symbolic representations. An algorithmic Dada, breaking conventional links between intellectual meaning and emotional response to sensed aesthetics, exploiting gaps between content and experience. Moten argues such breaks are spaces for new politics to develop4.

Keeping this in mind, another way of conceptualising the design of chatterbots, draws on my background in quantum computing. Through my ongoing research at the Royal College of Art, I have found that quantum concepts provide a unique lens to (re)assess uses and impacts of new technologies. It is not necessary to understand quantum computing to use or value this approach. Instead, I turn theorists who have teased out some resonances between between (quantum) physics and other systems.

Here for brevity, I turn solely to the concept of diffraction introduced by Harroway and subsequently developed by Barad. Diffraction is a physical process by which a seemingly coherent signal consisting of light or matter splits into several beams travelling in different directions. Diffraction stands up to reflection, by mapping where the effects of differences occur. Reflection displaces the existing, whereas diffractions (re)imagines and (de)constructs. This material dispersion is contingent on the constituent components of the signal (including any noise) and the apparatus.

Apparatus diffracts white light into the components of the visible spectrum.

Apparatus diffracts white light into the components of the visible spectrum.

Chatterbots may diffract canonical histories and stories into strange new forms. For instance a deep learning algorithm generating text at character level, trained on, for instance, a data set of speeches by western world leaders, might be expected to replicate typical western rhetoric. Whereas by experimenting with the parameters of the neural net and the quality or quantity of the data set, ‘good noise’ may form the signals, diffracting a canonical history into multiple worlds5.

Diffraction plays a crucial role in storytelling in two ways. Firstly, it provides a model for how dominant narratives become dominant in the first place. At any time, a multitude of signals are present for any phenomena, containing an ecology of histories, potentialities and fragments. Power structures enable certain discourses to be given more weight than others. These discourses are repeated and strengthened and are materialized. Alternative narratives that were present in the sea (for instance correctly identifying the NSA drone targets as civilians), cancel each other out and are diminished. However, unconventional uses of machine learning algorithms may fracture this. Particularly when the data set modelling a phenomena is incomplete or has unusual features. By shifting the apparatus and altering the input, diffraction may strengthen hidden patterns, splitting up dominant ones.

I have been experimenting with noisy chatterbots in my current project. Britbot is a netbased chatterbot that speaks to members of the public on topics from the UK government’s citizenship test, and gradually learns from what they say. The citizenship test was chosen as it represents a dominant narrative and a clear line between what might be considered British and foreign. Britbot blurs this line. Mapping the content of the current version of the test reveals a largely white male privileged version of British history and culture. It contains just 16% women. A discussion of visual art and a list of British directors include zero women and zero ethnic minorities. Sport is the only area diverse in terms of race, gender, disabilities and class. As it stands there are no LGBTQ people or issues mentioned explicitly in the entire textbook. And as far I as I have been able to determine at least 50% of the people mentioned grew up with private educated or in very wealthy households.

The text data used to train Britbot was scraped from various websites featuring topics from the test. Since this corpus is not entirely conversational and far from complete in terms of possible conversations (areas), it provides a noisy source that can be diffracted into strange new forms of collective and individual national identities. Britbot is live until Dec 2018 at www.britbot.org.

References:

- http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/06/when-will-alexa-google-assistant-and-other-chatbots-finally-talk-us-real-people↩

- In 'Talking on the water: Conversations about Nature and Creativity', J. White, Trinity University Press 2016.↩

- 'Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases' A. Caliskan et al, Science, 2017.↩

- 'In The Break: The Aesthetics Of The Black Radical Tradition', F. Moten, University of Minnisota Press, 2003.↩

- I like to think of this as the garden depicted in The Garden of Forking Paths (Penguin Modern), J L Borges, Penguin Classics, 2018.↩