The challenges and opportunities of ethical AI

Josh Cowls, Luciano Floridi, and Mariarosaria Taddeo

Data Ethics Group, The Alan Turing Institute Digital Ethics Lab, Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford

Introduction

Whether or not AI will have a major impact on society is no longer up for debate. Instead, it is time to consider whether this impact will be positive or negative, for whom, in which ways, in which places, and on what timescale; in short, the key questions now are how, where, when and by whom the impact of AI will be felt.

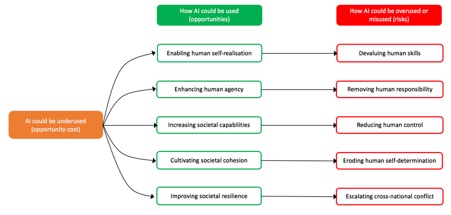

In this short paper we introduce what we think are the five central opportunities for society that AI offers. In each case, AI can be used to foster human nature and its potentialities, thus creating _opportunities_; underused, thus creating _opportunity costs_; or overused and misused, thus creating _risks_. The positive, innovative use of AI would allow society to take advantage of the great opportunities that the technology offers. However, fear, ignorance, misplaced concerns or excessive reaction may lead a society to underuse AI technologies below their full potential. This might include, for example, heavy-handed or misconceived regulation, under-investment, or a public backlash akin to that faced by earlier, potentially beneficial technologies like genetically modified crops and nuclear power.

As a result, the benefits offered by AI technologies may not be fully realised by society. These dangers often arise for accidental reasons, unintended consequences, and good intentions gone awry. However, we must also consider the risks associated with wilful misuse of AI technologies, grounded, for example, in misaligned incentives, greed, adversarial geopolitics, or malicious intent. Everything from email scams to full-scale cyber-warfare may be accelerated or intensified by the malicious use of AI technologies (Taddeo, 2017). And new evils may be made possible (King et. al, 2018).

Therefore, the possibility of social progress represented by the opportunities mentioned above must be weighed against the risk that malicious manipulation will be enabled or enhanced by AI. We summarise these opportunities, the equivalent risks, and the opportunity cost of underusing AI in Figure A below. In the remainder of this paper we offer a more detailed explanation of each.

1. Who we can become: enabling human self realisation, without devaluing human skills

AI may enable self-realisation, by which we mean the ability for people to flourish in terms of their own characteristics, interests, potential abilities or skills, aspirations, and life projects. Just as inventions such as the washing machine liberated people from the drudgery of domestic work, the “smart” automation of other mundane aspects of life may free up yet more time for cultural, intellectual and social pursuits or more interesting work. More AI may mean more human life spent more intelligently. The risk in this case is not the obsolescence of some old skills and the emergence of new ones per se, but the pace at which this is happening, the impacts of which are felt at both the individual and societal level. At the level of the individual, jobs are often intimately linked to personal identity, self-esteem, and social standing, all factors that may be adversely affected by redundancy, even putting to one side the potential for severe economic harm. Furthermore, at the level of society, the deskilling of sensitive, skill-intensive domains, such as health care diagnosis or aviation, may create dangerous vulnerabilities in the event of AI malfunction or an adversarial attack. Fostering the development of AI in support of new skills, while anticipating and mitigating its impact on old ones, will require both close study and potentially radical ideas, such as the proposal for some form of “universal basic income”, which is growing in popularity and experimental use.

2. What we can do: enhancing human agency, without removing human responsibility

AI is providing a growing reservoir of “smart agency”. Put at the service of human intelligence, such a resource can hugely enhance human agency. We can do more, better, and faster, thanks to the support provided by AI. In this sense of “Augmented Intelligence”, AI could be compared to the impact that engines have had on our lives. The larger the number of people who will enjoy the opportunities and benefits of such a reservoir of smart agency “on tap”, the better our societies will be. Responsibility is therefore essential when we decide how to develop, use, and share the benefits of AI. The absence of such responsibility may occur not just because we have the wrong socio-political framework, but also because of a “black box” mentality, according to which AI systems for decision-making are seen as being beyond human understanding and hence control. These concerns apply not only to high-profile cases, such as deaths caused by autonomous vehicles, but also to more commonplace but still significant uses, such as in automated decisions about parole or creditworthiness. All the same, human agency may be ultimately supported, refined and expanded in the age of AI by embedding “facilitating frameworks”, designed to improve the likelihood of morally good outcomes, in the set of functions that we delegate to AI systems. Therefore, if they are designed efficiently, AI systems could amplify and strengthen shared moral systems.

3. What we can achieve: increasing societal capabilities, without reducing human control

Artificial intelligence offers myriad opportunities for improving and augmenting the capabilities of individuals and society at large. Whether by preventing and curing diseases or optimising transportation and logistics, the use of AI technologies presents countless possibilities for reinventing society, by radically enhancing what humans are collectively capable of. More AI may support better coordination, and hence more ambitious goals. Human intelligence augmented by AI could find new solutions to old and new problems, from a fairer or more efficient distribution of resources to a more sustainable approach to consumption. Yet precisely because such technologies have the potential to be so powerful and disruptive, they also introduce proportionate risks. It may seem that we need no longer be ‘in the loop’ if and when we delegate our tasks to AI. However, if we rely on the use of AI technologies to augment our own abilities in the wrong way, we may delegate important tasks and decisions to autonomous systems that should remain at least partly subject to human supervision and choice. This in turn may reduce our ability to monitor the performance of these systems or preventing or redressing errors or harms that arise. These potential harms may even accumulate and become entrenched, as more and more functions are delegated to artificial systems. We must therefore strike a balance between pursuing the ambitious opportunities offered by AI to improve human life, on the one hand, and, ensuring that we remain in control of these major developments and their effects on the other.

4. How we can interact: cultivating societal cohesion, without eroding human self-determination

From climate change and antimicrobial resistance to nuclear proliferation and fundamentalism, global problems increasingly have high degrees of “coordination complexity”, meaning that they can be tackled successfully only if all stakeholders co-design and co-own the solutions. AI, with its data-intensive, algorithmic-driven solutions, can hugely help to deal with such coordination complexity, supporting more societal cohesion and collaboration. For example, efforts to tackle climate change have exposed the major challenges involved in creating a cohesive response. The scale of this challenge is such that we may soon need to decide between engineering the climate directly and engineering society to encourage a drastic cut in harmful emissions. This latter option might be undergirded by an algorithmic system to cultivate societal cohesion. Such a system would not be imposed from the outside; it would be the result of a self-imposed choice, not unlike our choice of not buying chocolate if we need to be on a diet. “Self-nudging” to behave in socially preferable ways is the best form of nudging. It is the outcome of human decisions and choices, but it can rely on AI solutions to be implemented. Yet the risk is that AI systems may erode human self-determination, as they may lead to unplanned and unwelcome changes in human behaviours to accommodate the routines that make automation work and people’s lives easier. AI’s predictive power and relentless nudging, even if unintentional, should support human self-determination and foster societal cohesion, not undermine human flourishing or dignity.

5. How we can strengthen: improving societal resilience, without escalating cross-national conflict

The final opportunity we must consider relates to the strength and security of society. AI can improve this by increasing the resilience and robustness of critical systems, combined with counter-threat strategies. Thanks to its autonomy, fast-paced threat-analysis, and decision-making capabilities, AI can enable systems’ verification and patching, and counter incoming threats by exploiting the vulnerabilities of antagonist systems (Defence Science Board, 2016). However, two related challenges may hamper AI’s potential for security. One is escalation. AI can refine strategies and launch more aggressive counter operations. This may snowball into an intensification of attacks and responses, which, in turn, may threat key infrastructures of societies (Taddeo, 2017). The solution is to use AI to strengthen deterrence strategies and discourage opponents before they attack, rather than mitigating the consequences of successful attacks afterwards. The other challenge is lack of control. Pervasive distribution, multiple interactions, and fast-pace execution will make the control of the performance of AI systems progressively less effective, while increasing the risks for unforeseen consequences and errors. Regulations may extenuate the lack of control, by ensuring that responses are proportional, targets are legitimate, and that behaviour is responsible. But it is crucial to start shaping and enforcing policies and norms for the use of AI in security as soon as possible, while the technology is still nascent. The alternative is an AI-weaponised, unsafe and unstable cyberspace.

### Conclusion

As serious as each of these risks undoubtedly are, the good news is that there is a wide array of organisations already working to develop policies, best practices, and technological solutions to address the challenges and secure the benefits of AI for society. Initiatives like AI4People, the IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems, and the Partnership on Artificial Intelligence to Benefit People and Society have convened representatives from across society, and policymaking bodies such as the UK’s Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation and the European Commission’s High Level Expert Group on AI have pledged to address these challenges head-on.

Winston Churchill once said that “we shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us”. This applies to AI as well. We must design and use AI ethically, securely, and with human wellbeing in mind – and we must do so now.

References:

- Defence Science Board (2016, June). "Summer Study on Autonomy," *US Dep. Def*.

- King, T., Aggarwal, N., Taddeo, M., and Floridi, L (2018, May, 22), Artificial Intelligence Crime: An Interdisciplinary Analysis of Foreseeable Threats and Solutions. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3183238

- Taddeo, M. (2017). The limits of deterrence theory in cyberspace. Philos. Technol. 2017, 1--17.